Image Courtesy of U.S. Geological Survey

Silver Tells a Story of Early Earth: Water Here Since Planet's Very Early Days

Tiny variations in the isotopic composition of silver in meteorites and Earth rocks are helping scientists put together a timetable of how our planet was assembled, beginning 4.568 billion years ago.

Results of a new study, funded by the National Science Foundation (NSF) and published this week in the journal Science, indicate that water and other key volatiles may have been present in at least some of Earth's original building blocks, rather than acquired later from comets, as some scientists have suggested.

"These results have significant implications for our understanding of the processes that accompanied accretion and formation of the proto-Earth, and the means by which volatile-rich materials like water were acquired," says Stephen Harlan, program director in NSF's Division of Earth Sciences. "Water may have been present since very early in the history of our planet."

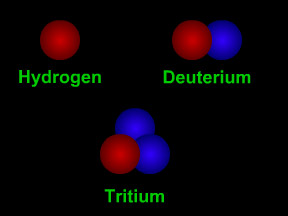

Compared to the solar system as a whole, Earth is depleted in volatile elements, such as hydrogen, carbon, and nitrogen, which likely never condensed on planets formed in the inner, hotter, part of the solar system.

Earth is also depleted in moderately volatile elements, such as silver.

"A big question in the formation of the Earth is when this depletion occurred," says paper co-author Richard Carlson of the Carnegie Institution for Science in Washington, D.C. "That's where silver isotopes can really help."

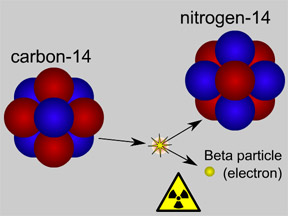

Silver has two stable isotopes, one of which, silver-107 was produced in the early solar system by the rapid radioactive decay of palladium-107.

Palladium-107 is so unstable that virtually all of it decayed within the first 30 million years of the solar system's history.

Silver and palladium differ in their chemical properties.

Silver is the more volatile of the two, whereas palladium is more likely to bond with iron.

These differences allowed the Carnegie researchers--including lead author Maria Schönbächler (a former Carnegie Institution postdoctoral scientist now at the University of Manchester), Erik Hauri, Mary Horan and Tim Mock--to use the isotopic ratios in primitive meteorites and rocks from Earth's mantle to determine the history of Earth's volatiles relative to the formation of its iron core.

Other evidence from hafnium and tungsten isotopes indicates that the core formed between 30 to 100 million years after the origin of the solar system.

"We found that the silver isotope ratios in mantle rocks from the Earth exactly matched those in primitive meteorites," says Carlson.

"But these meteorites have compositions that are very volatile-rich, unlike the Earth, which is volatile-depleted."

The silver isotopes also presented another riddle, suggesting that Earth's core formed about five to 10 million years after the origin of the solar system, much earlier than the date from the hafnium-tungsten results.

The group concludes that these contradictory observations can be reconciled if Earth first accreted volatile-depleted material until it reached about 85 percent of its final mass, and then accreted volatile-rich material in the late stages of its formation, about 26 million years after the solar system's origin.

The addition of volatile-rich material could have occurred in a single event, perhaps the giant collision between the proto-Earth and a Mars-sized object thought to have ejected enough material into Earth's orbit to form the Moon.

The results of the study support a 30-year old model of planetary growth called "heterogeneous accretion," which proposes that the Earth's building blocks changed in composition as the planet accreted.

Carlson adds that it would have taken just a small amount of volatile-rich material similar to primitive meteorites added during the late stages of Earth's accretion to account for all the volatiles, including water, on Earth today.

This work was also supported by the Carnegie Institution for Science.

Text above is courtesy of the National Science Foundation