Images courtesy SOHO (ESA & NASA). Animation by Windows to the Universe staff (Randy Russell).

Rotation of the Sun

The Sun, like most other astronomical objects (planets, asteroids, galaxies, etc.), rotates on its axis. Unlike Earth and other solid objects, the entire Sun doesn't rotate at the same rate. Because the Sun is not solid, but is instead a giant ball of gas and plasma, different parts of the Sun spin at different rates.

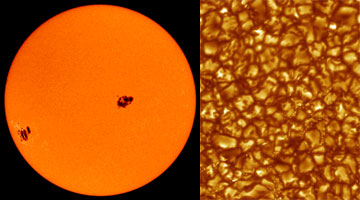

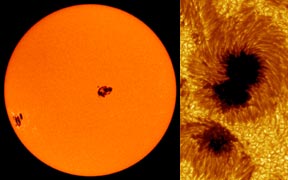

We can tell how quickly the surface of the Sun is rotating by observing the motion of structures, such as sunspots, on the Sun's visible surface. The regions of the Sun near its equator rotate once every 25 days. The Sun's rotation rate decreases with increasing latitude, so that its rotation rate is slowest near its poles. At its poles the Sun rotates once every 36 days!

The interior of the Sun does not spin the same way as does its surface. Scientists believe that the inner regions of the Sun, including the Sun's core and radiative zone, do rotate more like a solid body. The outer parts of the Sun, from the convective zone outward, rotate at different rates that vary with latitude. The boundary between the inner parts of the Sun that spin together as a whole and the outer parts that spin at different rates is called the "tachocline".

The behavior of the Sun's magnetic field is strongly influenced by the combination of convective currents, which bring the charged plasma from deep within the Sun to the Sun's surface, and the differential rotation of the outer layers of the Sun. The complex, swirling motions that result make a tangled mess of magnetic field lines at the Sun's surface. Differential rotation is apparently the main driver of the 11-year sunspot cycle and the associated 22-year solar cycle. The notion that differential rotation and convective motion drive these cycles was first put forth in 1961 by the American astronomer Horace Babcock, and is now known as the Babcock Model.

(Note: If you cannot see the animation of the rotating Sun on this page you may need to download the latest QuickTime player.)