Click on image for full size

Image courtesy Argonne National Laboratory

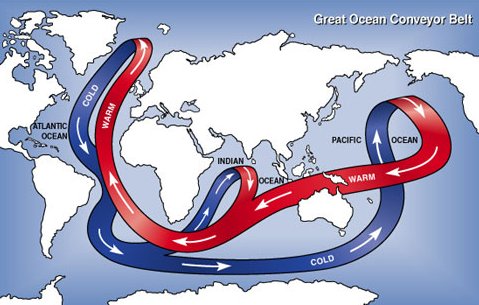

Thermohaline Circulation: The Global Ocean Conveyor

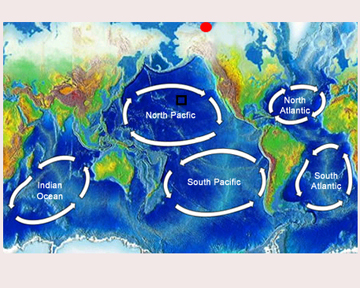

The world has several oceans, the Pacific, the Atlantic, the Indian, the Arctic, and the Southern Ocean. While we have different names for them, they are not really separate. There are not walls between them. Water is able to move freely between oceans. They are all connected in one global ocean.

If you visit a shoreline and watch the ocean, you will see water on the move. Waves crash on the beach. Tides move water back and forth twice a day, longshore currents and rip tides transport unobservant swimmers far away from their beach towels. These are some of the small scale ways that seawater moves. Seawater moves in larger ways too. There is a large-scale pattern to the way that seawater moves around the world ocean. This pattern is driven by changes in water temperature and salinity that change the density of water. It is known as the Global Ocean Conveyor or thermohaline circulation. It affects water at the ocean surface and all the way to the deep ocean. It moves water around the world.

The Global Ocean Conveyor moves water slowly, 10 cm per second at most, but it moves a lot of water. One hundred times the amount of water that is in the Amazon River is being transported by this huge slow circulation pattern. The water moves mainly because of differences in relatively density. Water that is more dense sinks below water that is less dense. Two things affect the density of seawater: temperature and salinity.

Cold water is denser than warm water.

- Water gets colder when it loses heat to the atmosphere, especially at high latitudes.

- Water gets warmer when it is heated by incoming solar energy, especially at low latitudes.

Saltier water is denser than less salty water.

- Water gets saltier if rate of evaporation is high.

- Water gets less salty if there is an influx of freshwater either from melting ice or precipitation and runoff from land.

In the Atlantic, the circulation of seawater is driven mainly by temperature differences right now. Water heated near the equator travels at the surface of the ocean north into high latitudes where it loses some heat to the atmosphere (keeping temperatures in Northern Europe and North America relatively mild). The cooled water sinks to the deep ocean and travels the world ocean, possibly not surfacing for hundreds or even as much as a thousand years.

There is concern that as the Arctic warms and more sea ice melts, the influx of freshwater will make the seawater at high latitudes less dense. The less dense water will not be able to sink and circulate throughout the world. This may stop the global ocean conveyor and change the climate of the European and North American continents.