Click on image for full size

Windows to the Universe original image

The Deep Waters of the Ocean

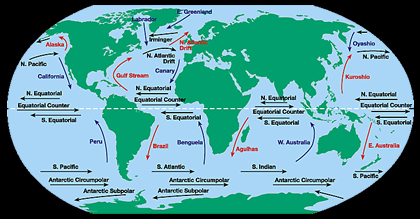

Have you ever taken a vacation near an ocean? Maybe you went swimming or surfing in the water, maybe you went deep sea fishing or on a glass bottom boat ride. These activities all take place in the surface waters of the ocean. But did you know that most of the water in the ocean (90% by volume) is actually found below the surface layer of the ocean? Most people will never see the deep waters of the ocean...they are just too deep! The pycnocline, characterized by a rapid change of density, separates the surface layer of the ocean from the deep ocean. Typical deep ocean water has a temperature of about 3 degrees Celsius and a salinity measuring about 34-35 psu.So, where do these deep waters come from? The biggest source of deep water is surface water that sinks in the North Atlantic Ocean. The Gulf Stream current brings highly saline water northward (salinity is high in mid-latitudes where evaporation is high and precipitation is low). Cold water from the north (Labrador and Irminger currents) meets the Gulf Stream and the water gets mixed. This cold, salty mixture can be dense enough to sink into the depths of the ocean.

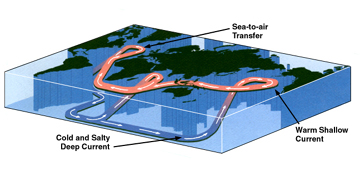

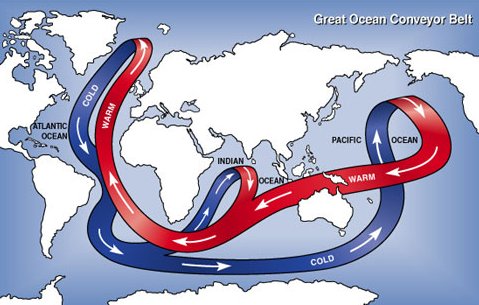

While surface currents are driven mainly by wind, deep water circulation is driven by gravity. Cold and salty ocean surface water in the North Atlantic and elsewhere will slowly sink downward until it reaches a level of equal density. If the water is more dense (colder and/or saltier) then any other water in the deep ocean, it will sink all the way to the sea floor. Once the water reaches a level of equal density, the water spreads out. So in this way the deep ocean is stratified into horizontal layers, with water of higher and higher density sinking to deeper and deeper layers. The water that sinks in the North Atlantic flows all the way past the equator into the Southern Hemisphere. The water then flows past Antarctica and into the Pacific and Indian Oceans. Here, some of the deep waters are warmed and so rise again to the surface and to the surface circulation system. This conveyor belt cycling (pictured above) of the ocean waters is a simplification of the global ocean circulation. Still, it helps to show the basic idea of ocean water circulation from the surface to the depths of the ocean back to the surface again. In reality, deep water circulation is interrupted or diverted by ridges, rises and other underwater obstacles.

Deep water circulation is driven by density differences. Density is in turn dependent on the temperature and salinity of the water sample. Because of this dependence, deep water circulation is sometimes referred to as thermohaline circulation. Thermohaline circulation is very slow. Once water sinks from the surface, it can spend a long time away from the surface until that water rises again to become part of surface circulation. Some scientists estimate that the residence time of deep water, the time spent away from the surface, can be about 200-500 years for the Atlantic Ocean and 1,000-2,000 years for the Pacific Ocean.

Deep water circulation and surface currents are both ways in which heat distribution happens on Earth. These two types of water movement keep the equatorial region from overheating and the poles from becoming permanent frozen regions.

Deep waters contain a lot of nutrients such as phosphates, nitrates, and carbonates. Regions of upwelling of these deep waters are important for ocean productivity at the surface. When the nutrient-enriched deep water does well up to the surface, high plankton productivity and abundant fish can be found.