- CLIMATE AND GLOBAL CHANGE

- What Is Climate?

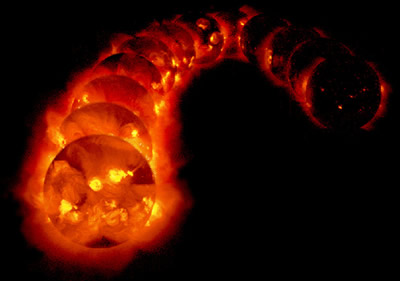

- What Controls Climate?

- Paleoclimates

- Our Changing Planet

- Effects of Climate Change

- Polar Regions

- Climate Events

- Clouds in Climate

- Energy Interactive

- IPCC

- Slowing Global Warming

- Climate Models

- Climate News

- Games/Activities

- Multimedia

- Links

- Web Seminars

- Climate Literacy

- Copenhagen Summit

Climate and Global Change

Warm near the equator and cold at the poles, our planet is able to support a variety of living things because of its diverse regional climates. The average of all these regions makes up Earth's global climate. Climate has cooled and warmed throughout Earth history for various reasons. Rapid warming like we see today is unusual in the history of our planet. The scientific consensus is that climate is warming as a result of the addition of heat-trapping greenhouse gases which are increasing dramatically in the atmosphere as a result of human activities.

Please log in

Science Blogs

Real Climate: climate science from climate scientists

Windows to the Universe, a project of the National Earth Science Teachers Association, is sponsored in part is sponsored in part through grants from federal agencies (NASA and NOAA), and partnerships with affiliated organizations, including the American Geophysical Union, the Howard Hughes Medical Institute, the Earth System Information Partnership, the American Meteorological Society, the National Center for Science Education, and TERC. The American Geophysical Union and the American Geosciences Institute are Windows to the Universe Founding Partners. NESTA welcomes new Institutional Affiliates in support of our ongoing programs, as well as collaborations on new projects. Contact NESTA for more information.