Courtesy of NASA

“Missing” Heat May Affect Future Climate Change

Current observational tools cannot account for roughly half of the heat that is believed to have built up on Earth in recent years, according to a "Perspectives" article in this week's issue of the journal Science.

Scientists at the National Center for Atmospheric Research (NCAR) in Boulder, Colo., warn that satellite sensors, ocean floats, and other instruments are inadequate to track this "missing" heat, which may be building up in the deep oceans or elsewhere in the climate system.

"The heat will come back to haunt us sooner or later," says NCAR scientist Kevin Trenberth, the article's lead author.

"The reprieve we've had from warming temperatures in the last few years will not continue. It is critical to track the build-up of energy in our climate system so we can understand what is happening and predict our future climate."

The authors suggest that last year's rapid onset of El Niño, the periodic event in which upper ocean waters across much of the tropical Pacific Ocean become significantly warmer, may be one way in which the solar energy has reappeared.

The research was supported by the National Science Foundation (NSF), NCAR's sponsor, and by NASA.

"The flow of energy through the climate system is a key issue in understanding climate change," says Eric DeWeaver, program director in NSF's Division of Atmospheric and Geospace Sciences, which funds NCAR. "It poses a major challenge to our observing systems."

Trenberth and his co-author, NCAR scientist John Fasullo, focused on a central mystery of climate change.

Whereas satellite instruments indicate that greenhouse gases are continuing to trap more solar energy, or heat, scientists since 2003 have been unable to determine where much of that heat is going.

Either the satellite observations are incorrect, says Trenberth, or, more likely, large amounts of heat are penetrating to regions that are not adequately measured, such as the deepest parts of the oceans.

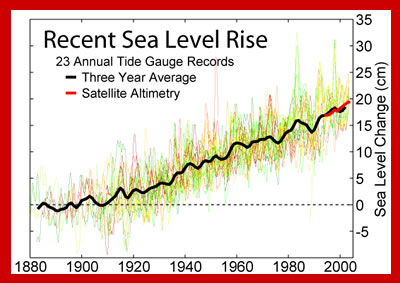

Compounding the problem, Earth's surface temperatures have largely leveled off in recent years. Yet melting glaciers and Arctic sea ice, along with rising sea levels, indicate that heat is continuing to have profound effects on the planet.

Trenberth and Fasullo explain that it is imperative to better measure the flow of energy through Earth's climate system.

For example, any geoengineering plan to artificially alter the world's climate to counter global warming could have inadvertent consequences, which may be difficult to analyze unless scientists can track heat around the globe.

Improved analysis of energy in the atmosphere and oceans can also help researchers better understand and possibly even anticipate unusual weather patterns, such as the cold outbreaks across much of the United States, Europe, and Asia over the past winter.

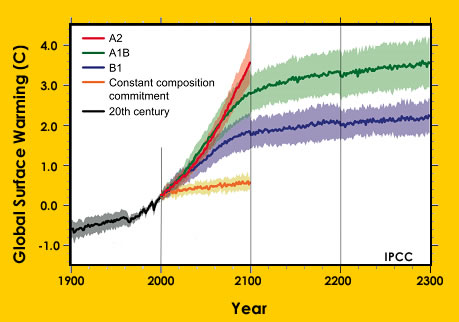

As greenhouse gases accumulate in the atmosphere, satellite instruments show a growing imbalance between energy entering the atmosphere from the sun and energy leaving from Earth's surface. This imbalance is the source of long-term global warming.

But tracking the growing amount of heat on Earth is far more complicated than measuring temperatures at the planet's surface.

The oceans absorb about 90 percent of the solar energy that is trapped by greenhouse gases. Additional amounts of heat go toward melting glaciers and sea ice, as well as warming the land and parts of the atmosphere.

Only a tiny fraction warms the air at the planet's surface.

Satellite measurements indicate that the amount of greenhouse-trapped solar energy has risen over recent years while the increase in heat measured in the top 3,000 feet of the ocean has stalled.

Although it is difficult to quantify the amount of solar energy with precision, Trenberth and Fasullo estimate that, based on satellite data, the amount of energy build-up appears to be about 1.0 watts per square meter or higher, while ocean instruments indicate a build-up of about 0.5 watts per square meter.

That means about half the total amount of heat is unaccounted for.

A percentage of the missing heat could be illusory, the result of imprecise measurements by satellites and surface sensors or incorrect processing of data from those sensors, the authors say.

Until 2003, the measured heat increase was consistent with computer model expectations. But a new set of ocean monitors since then has shown a steady decrease in the rate of oceanic heating, even as the satellite-measured imbalance between incoming and outgoing energy continues to grow.

Some of the missing heat appears to be going into the observed melting of ice sheets in Greenland and Antarctica, as well as Arctic sea ice.

Much of the missing heat may be in the ocean. Some heat increase can be detected between depths of 3,000 and 6,500 feet (about 1,000 to 2,000 meters), but more heat may be deeper still beyond the reach of ocean sensors.

Trenberth and Fasullo call for additional ocean sensors, along with more systematic data analysis and new approaches to calibrating satellite instruments, to help resolve the mystery.

The Argo profiling floats that researchers began deploying in 2000 to measure ocean temperatures, for example, are separated by about 185 miles (300 kilometers) and take readings only about once every 10 days from a depth of about 6,500 feet (2,000 meters) up to the surface.

Plans are underway to have a subset of these floats go to greater depths.

"Global warming at its heart is driven by an imbalance of energy: more solar energy is entering the atmosphere than leaving it," Fasullo says.

"Our concern is that we aren't able to entirely monitor or understand the imbalance. This reveals a glaring hole in our ability to observe the build-up of heat in our climate system."

Text above is courtesy of the National Science Foundation