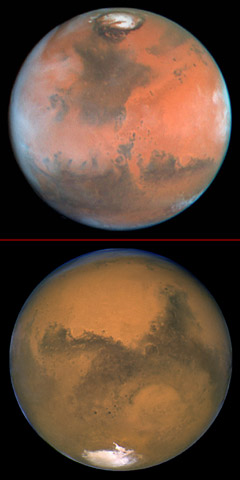

Click on image for full size

Images courtesy Phil James (Univ. Toledo), Todd Clancy (Space Science Inst., Boulder, CO), Steve Lee (Univ. Colorado), and NASA [North Pole image]; and NASA, J. Bell (Cornell U.) and M. Wolff (SSI) [South Pole image].

Mars Polar Regions

The North and South Poles on Mars are similar to the polar regions on Earth in many ways. They are the coldest places on the planet, with wintertime temperatures dipping to a frigid -150° C (about -238° F). Both poles have ice caps made primarily of water ice. The ice caps expand and retreat in size with the changing Martian seasons. Scientists believe that changes in the Martian climate over long time periods have caused the polar ice caps to shrink and grow, and even disappear at times, just like on Earth.

The Italian astronomer Giovanni Cassini was the first to observe one of the polar caps of Mars in 1666. Christiaan Huygens, a Dutch astronomer, produced the first drawings of the southern ice cap in 1672. Giacomo Filippo Maraldi, Cassini's nephew, was the first to observe both polar caps in 1719 and noted that the southern cap was not centered on the pole. In 1781 the British astronomer William Herschel was the first to assert that the Martian polar caps were made of ice.

The Martian polar caps contain both water ice and "dry ice" (frozen carbon dioxide). Most of the mass of the polar caps is water ice. The dry ice forms a relatively thin layer on top of the water ice. Mars has seasons that are similar to Earth's, for its rotational axis has a tilt remarkably similar to that of our home planet (25.19° for Mars, compared to 23.45° for Earth). In the winter, carbon dioxide gas from the atmosphere freezes out at the poles, adding a coating of dry ice to the polar caps. This dry ice layer is only about 1 meter thick in the North, and about 8 meters deep in the South. The dry ice layer sublimates away completely in the northern summer, while the thicker coating is partially retained throughout the summertime.

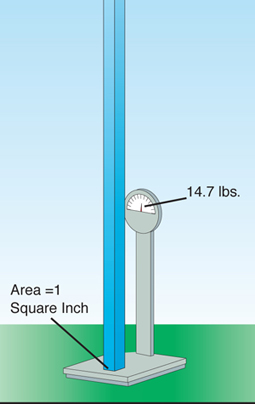

The water ice portions of both polar caps have thicknesses as great as 3 kilometers. The northern cap is roughly 1,100 km in diameter, while the southern cap is about 350 km across. The geographic extend of each ice cap grows by several times in the winter when the dry ice is deposited. So much carbon dioxide freezes out of the atmosphere to form the extended polar caps that atmospheric pressure on Mars can vary by as much as one-third! The portions of the ice caps that do not wax and wane with the changing seasons are called the Residual Caps or the Permanent Caps. For comparison, the Residual Caps combined contain slightly more water than the Greenland ice sheet on Earth (and far, far less than the vastly larger Antarctic ice sheet). If all of the polar water ice on Mars were melted and spread evenly over the surface, it would coat the Red Planet to a depth of about 20 meters.

Both polar caps exhibit beautiful layered features that result from seasonal melting and deposition of ice along with dust from the famous Martian dust storms. These layers may provide clues about the evolution of the Martian climate, much as tree ring patterns and ice core data do on Earth. Both polar caps also have astonishing grooved features cut into the ice, likely caused by patterns in the winds flowing between the cold ice caps and the warm surrounding terrain. Differential melting of ice depending on the amount of dust it contains probably contributes to the formation of these grooves as well. Besides the ice caps themselves, the ground near the poles appears to have large deposits of ice buried beneath and within the soil.

In modern times the Martian ice caps have received attention from scientists because of their water ice. Water is a key ingredient for life as we know it, so "follow the water" has been a rallying cry for astrobiologists seeking clues about the possibility of life on Mars, either in the past or the present day. Sadly, NASA's Mars Polar Lander was lost in December 1999 as it attempted to land near the Martian South Pole. However, a new mission, the Phoenix Mars Lander is slated to touch down near the North Pole of the Red Planet in May 2008. Hopefully Phoenix will provide new insights about the fascinating poles of Mars!