Click on image for full size

Courtesy of Scripps Institution of Oceanography, UC San Diego

Finding Answers in the Clouds

News story originally written on May 21, 2008

If you were fortunate to spend time recently in the Maldives, a collection of tropical islands in the central Indian Ocean, you may have seen a collection of tiny aircraft buzzing overhead. With a wingspan of about eight feet and weighing less than 50 pounds, one might mistake them for a set of remote control planes. But these aircraft are no hobbyist's toys--they are sophisticated autonomous unmanned aerial vehicles (AUAVs), and they are providing scientists with important insights into how air pollution shapes global warming.

A research consortium led by Professor V. Ramanathan of the Scripps Institute of Oceanography at the University of California, San Diego, first began using these AUAVs in Maldives about two years ago. Last week the team published a paper in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences outlining some of their findings.

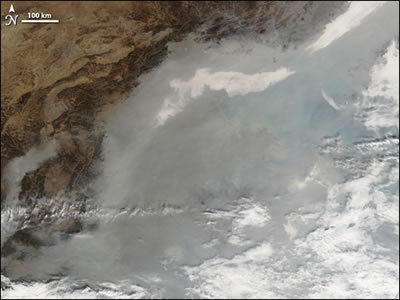

The Maldives are a good place to observe a phenomenon known as brown clouds, or very large plumes of air pollution that form particulate-laden haze and cumulus clouds. Brown clouds can be formed naturally during large forest fires, for example, but today there are several man-made brown clouds that last virtually year round as human activity generates smoke from power plants, automobiles, factories and other sources. These massive plumes travel high in the atmosphere where prevailing winds carry them over great distances. In the case of the Maldives, human activity in the Indian subcontinent causes a large brown cloud to drift down over the islands, giving scientists an opportunity to observe them.

For V. Ramanathan, a Scripps scientist who researches these brown clouds, the problem was how to observe them from the inside out. Ramanathan and his colleagues wanted to better understand how pollution alters the earth's albedo, or amount of sunlight that is reflected back out into space. Albedo impacts the earth's temperature, weather patterns and the broader climate.

"We are interested in finding the brightening effect of this pollution on the planet," Ramanathan said. Satellites offer a glimpse from above and ground observations give some information, but to understand the albedo level of these brown clouds, the best method is to fly into them with sophisticated instruments. Manned aircraft can do the job, but the cost can be between $5,000 to $10,000 an hour, greatly limiting the amount of time they can be available to gather data.

Enter the Manta AUAV. Built by Advanced Ceramics Research of Tucson, Ariz., these AUAVs carry miniaturized instrument packages developed by members of Ramanathan's team, including Greg Roberts, M V Ramana and Craig Corrigan. These instruments are capable of measuring solar radiation, cloud-drop size and concentrations, particle size and concentrations, turbulence, humidity and temperature. The craft can remain airborne for several hours, travel hundreds of miles and as high as 15,000 feet. They are also substantially cheaper to operate than manned aircraft, meaning they can make more flights and observations.

In the Maldives experiments, each flight of AUAVs consisted of three aircraft flying in a parallel formation at different altitudes. This allowed the researchers to observe albedo levels from above the clouds and link the observed variations in cloud albedo to variations in cloud properties captured by the second UAV flying through the cloud and to pollution particles entering the clouds from below observed by the third UAV flying below the cloud. While in flight, the AUAVs followed a pre-arranged flight pattern, but a pilot on the ground could also guide the lead aircraft using a live video feed into different areas of the clouds. The two other AUAVs then automatically followed the lead plane's direction.

These new capabilities have lead to important insights into how air pollution impacts our weather and climate. The team discovered, for example, that increased levels of air pollution have increased the atmosphere's albedo by a significant amount, resulting in more sunlight being reflected back into space. This research will help create more accurate climate models. It also suggests that air pollution is masking some of the impact of global warming by keeping the planet somewhat cooler. In addition, it suggests that as air pollution, which causes serious health problems, is reduced, the global climate will get even hotter.

Ramanathan believes these findings point to the need for further research into the relationship between air pollution and climate change, and that the use of automated unmanned sensors are a powerful tool for conducting that research. The Scripps team plans to use the AUAVs to study air pollution in southern California and in the atmosphere off the coast of China during the upcoming Olympic games.

"Our work in the Maldives has made us think about robotic measurements as the way of the future," he explained, "except it's here right now."

-NSF-