Click on image for full size

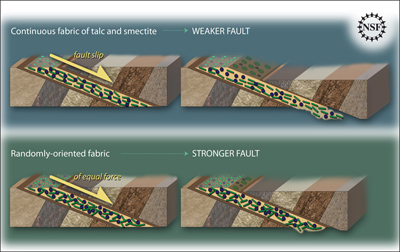

Credit: Zina Deretsky, NSF

It’s Not Your Fault – A Typical Fault, Geologically Speaking, That Is

News story originally written on December 16, 2009

Some geologic faults that appear strong and stable, slip and slide like weak faults, causing earthquakes. Scientists have been looking at one of these faults in a new way to figure out why.

In theory, low-angle normal faults, which dip less than 45 degrees, should not slip because, as stress and strain build up within the rocks, it’s easier for a new fault to form rather than for a low-angle fault to slip.

However, they do slip. Observations of actual low-angle faults have found that they move. Somehow they act more like weak faults, slipping and sliding. Scientists wanted to know how.

The evidence that suggests they should not slip comes from experiments on the friction of rocks in fault zones. These experiments test rock samples from fault zones by grinding a sample of the rock into a powder and then using an instrument that applies force to the powder. This measures the amount of force it takes to move a fault in this type of rock.

Recently, an unusual low-angle normal fault on the Italian Island of Elba allowed scientists to take a closer look at the rocks that make up faults. The fault sits exposed on the island’s beach so it is easy to gather large amounts of rock. While scientists usually only get to work with small bits of rock from faults that are collected by drilling below the surface, in this case they had an entire beach of rock to examine.

They found that the wafer-like rock was very weak in one direction. The wafers of rock slid almost like a deck of cards when pushed. They found that small patches of talc and clay minerals allow the rock to slide. When these minerals cover flakey surfaces in the rock, they cause even more sliding. This type of evidence wouldn’t be obvious if the rock samples were ground into a powder.

"These low-angle normal faults do not look like they will do anything but creep along, but they could have earthquakes," said scientist Chris Marone. "There are places in central Italy, for example, where faults like this have had small earthquakes.