Galileo Cruises the Inner Jovian System

The Galileo spacecraft, which has been orbiting Jupiter since 1995, will crash into the planet on September 21, 2003. The crash is not an accident! Scientists want to make sure Galileo will never accidentally crash into Jupiter's moon Europa, so they are destroying the spacecraft by crashing it into Jupiter. Scientists think there could be life on Europa, so they want to make sure that any microbes from Earth that may be riding on Galileo cannot infect Europa. Since the team of scientists and engineers controlling Galileo knew that it would be destroyed, they decided to send Galileo on a risky orbit close to Jupiter in November 2002. The space near Jupiter is filled with deadly radiation, and Galileo had stayed away from that area earlier in its mission. Mission planners didn't want Galileo to get fried! But on November 5, 2002, Galileo swung very close to Jupiter, deep within the planet's powerful radiation belts. Galileo was able to collect new data from this region that had never been measured before!

The animation below shows some of the information Galileo gathered on the November 2002 encounter (known to Galileo mission team members as the the "A34 pass"). You will need to have the latest version of the Flash player to see this animation. There is more information about the features shown in the animation further down this page.

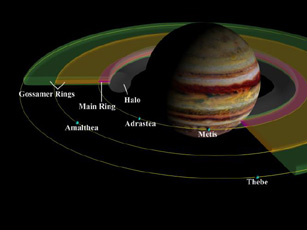

The animation shows the area close to Jupiter. Jupiter has moons; the five closest to the planet (Adrastea, Metis, Amalthea, Thebe, and Io) are shown here. Jupiter also has a series of rings, like the famous rings of Saturn. Jupiter's rings are much fainter and smaller than are Saturn's. Saturn's rings are mostly ice, while Jupiter's are made of dust. Jupiter has three major rings. The Main Ring is very narrow and thin. The Halo Ring is closer to Jupiter than the Main Ring, and is a larger, diffuse cloud of particles. Outside the Main Ring is the wispy Gossamer Ring. It has two parts: Thebe Gossamer Ring (further out) and the Amalthea Gossamer Ring (closer in). Data from Galileo led scientists to discover the source of the ring material! The material in the rings is fine dust hurled up from the surfaces of Jupiter's inner moons by meteor impacts.

Although it is nearly invisible, the dust of Jupiter's rings fills much of the space near the giant planet. There are other, even less visible, features near Jupiter that Galileo's instruments helped us detect. The space near Jupiter is seething with powerful magnetic fields, intense storms of radiation, and swarms of energetic particles.

There are three types of data shown in the animation: radiation, energy, and electron density. The radiation values represent the general background radiation levels, and are expressed in units of counts. This type of radiation is caused by bombardment by electrons. The energy values are measurements from an instrument designed to register counts per second of sulfur ions in a certain energy range. Sulfur from Io's atmosphere "leaks out" into the space around Jupiter. The sulfur in Io's atmosphere comes from eruptions of Io's many volcanoes. Scientists are uncertain whether the instrument for measuring sulfur ion counts worked correctly. It may have been "swamped" by electrons, and given false readings. That instrument, called the Energetic Particle Detector, also measured counts of many other types of ions in various different energy ranges. The third value shown is electron density. It is expressed in terms of electrons per cubic centimeter. There are a lot of electrons zooming around the space near Jupiter!

If you want to learn more of the details about these values, check out the text in the "Advanced" version of this page.