Click on image for full size

Courtesy of Jack Cook, WHOI (Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute)

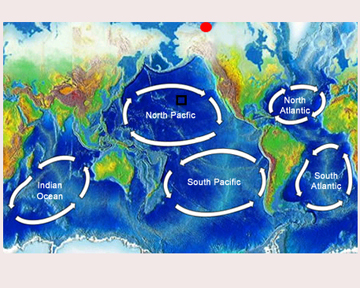

Arctic Ocean Currents

The majority of the world's population does not live in the Arctic. But even if you don't live in the Arctic, it is very important to understand how the Arctic Ocean works because it has an impact on surrounding areas and on global climate.If you look at the map on this page, you'll see how water moves through the Arctic Ocean. Cold, relatively fresh water comes into the Arctic Ocean from the Pacific Ocean through the Bering Strait. This water meets more fresh water from rivers and is swept into the Beaufort gyre where winds force the water into clockwise rotation. When winds slack off and the gyre weakens, fresh water leaks out of the gyre and into the North Atlantic Ocean (follow the blue lines on the illustration toward the bottom of the map). Of course, water can go both ways, and water does come into the Arctic Ocean from the North Atlantic (red lines on the map). This water is warmer and relatively salty. Because of its increased salinity, it is denser and sinks below Arctic waters.

The production of sea ice is also important to the layering of water in the Arctic Ocean. As sea ice is made near the Bering Strait, salt is released into the remaining non-frozen water. This non-frozen water becomes very salty and very dense and so it sinks below the cold, relatively fresh Arctic water, forming a layer known as the Halocline. The Halocline layer acts as a buffer between sea ice that has been made and the warm, salty waters that have come in from the Atlantic. Without the Halocline layer, the Atlantic waters would enter the Arctic and would begin to melt existing sea ice.

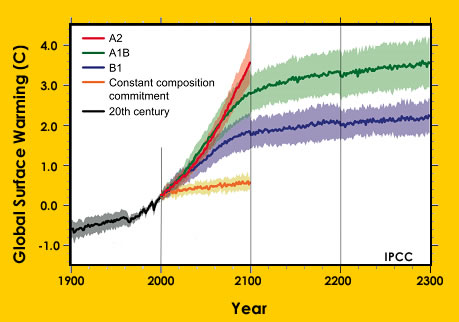

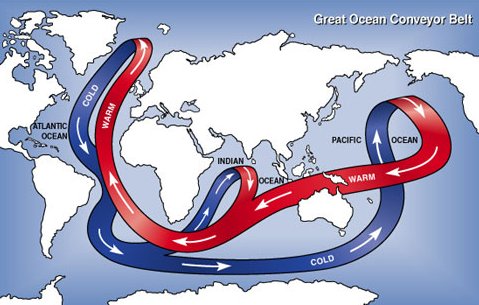

Scientists are very concerned about melting sea ice due to a different process -- global warming. Some fresh water flowing out of the Beaufort gyre and into the North Atlantic is expected as a result of natural processes. But melting sea ice due to global warming will increase the amount of fresh water in the Beaufort Gyre. That means more and more fresh water will spill out into the Atlantic, and many scientists think this could be a big problem that could cause major climate shifts in North America and Western Europe. Normally, these regions have mild climates because a system of ocean currents called the Global Ocean Conveyor carries heat as well as matter around the globe, and as it passes North America and Western Europe it warms those regions by releasing heat that it picked up in the tropics. If, however, there is a larger-than-normal layer of fresh water on top of the North Atlantic Ocean, scientists believe that it might act as a barrier preventing the warmer water from releasing its heat (therefore causing cooler temperatures in North America and Europe!).

There has been a lot of Arctic research in the last decade. The Arctic region is a difficult place to do research with high winds, very low temperatures, thick sea ice and even polar bears who probe (and try to eat!) instruments sitting on the ice. So in exploring Arctic currents, scientists have had to be creative. A very successful tool has been Ice-Tethered Profilers (ITP's). They measure temperature, salinity, and other water properties as they travel up and down a wire rope hanging down to 800 meters (~0.5 miles) into the Arctic Ocean. They can also measure surface currents as they drift through the Arctic. Although the floats won’t replace in-person measurements by scientists, they will allow year-round research in many areas that are too remote or dangerous for people (and they are polar bear proof!). In fact, ITP's make their measurements and send the data to computers via satellite so scientists can access the data from anywhere in the world. ITP's are just one more step forward in research that will hopefully shed more light on the Arctic Ocean, its currents, and its contributing role in regional and global climate.