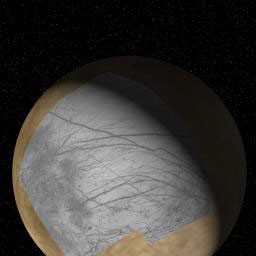

Click on image for full size

Image courtesy of NASA/Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory/Southwest Research Institute.

Results from the New Horizons Jupiter Flyby

The New Horizons spacecraft flew past Jupiter on February 28, 2007. New Horizons, which was launched in January 2006, is just over a year into its 9-year trek to Pluto. The spacecraft got a gravity assist from Jupiter as it hurtled past the the giant planet while traveling at a speed of 21 km/sec (47,000 mph). The slingshot boost from the massive planet will added 4 km/sec (9,000 mph) to New Horizon's speed, shaving years off its trip to distant Pluto.

The Jupiter encounter provided the New Horizons mission team with a great opportunity to hone their skills at controlling the spacecraft during a planetary flyby. Encounters such as this are complex; the spacecraft had to turn on and off its many instruments at just the right times, orient itself correctly as it zipped past the planet, and properly relay the data it gathered back to Earth. The mission scientists and engineers got a chance to practice their "planetary flyby choreography" at Jupiter as a warm up for the critical Pluto encounter eight years from now.

Mission scientists also gathered some great new data about Jupiter, for New Horizons carries a suite of state-of-the-art instruments and high resolution cameras. At closest approach, the spacecraft passed within about 2.3 million kilometers (1.4 million miles) of Jupiter.

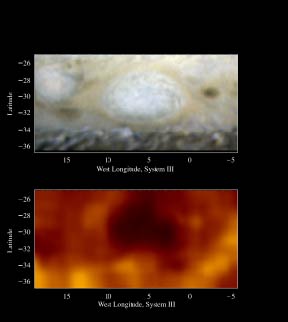

New Horizons snapped lots of great images of the constantly evolving clouds in Jupiter's atmosphere, and gave scientists their best look yet at the "Little Red Spot" - the "smaller cousin" of Jupiter's famous Great Red Spot. The Little Red Spot formed over the last several years via the merger of three smaller storms, and New Horizons became the first spacecraft to get a close-up view of this new weather system. The spacecraft also captured some great new images of Jupiter's rings. New Horizons isn't finished with its Jupiter observations yet; it will make measurements of the giant planet's vast magnetic field for weeks after the flyby as it zips along Jupiter's magnetotail. The magnetotail is a portion of the planet's immense magnetosphere that trails away the planet on the side away from the Sun. Magnetometers on the spacecraft will study Jupiter's magnetotail for somewhere between 45 and 70 days after the flyby.

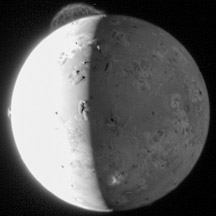

The spacecraft also captured some great images of some of Jupiter's many moons. It provided us with some new views of the icy surfaces of Europa and Ganymede. New Horizons also grabbed some of the best shots ever of volcanic eruptions on Io.