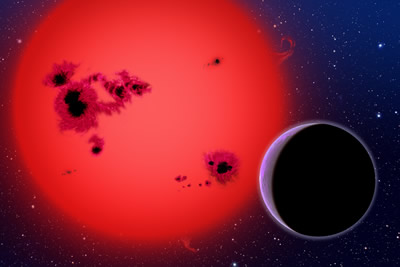

Click on image for full size

Original artwork by Windows to the Universe staff (Randy Russell) using images courtesy of NASA/JPL-Caltech/R. Hurt and NASA, ESA, and A. Feild (STScI).

What is a planet?

It may surprise you, but astronomers don't really have a good definition of a "planet". Because of this, Pluto is at the heart of a controversy about its status. Is Pluto a planet, or isn't it?

Scientists agree that the four rocky or "terrestrial" planets, Mercury, Venus, Earth and Mars, which orbit closest to the Sun, are all indeed planets. Likewise, the larger gas and ice giant planets, Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus and Neptune, are universally considered planets. But when we travel outward beyond the orbit of Neptune, to the icy fringes of our Solar System, the issue of planethood becomes a bit fuzzy.

Thousands of huge balls of ice orbit the Sun beyond Neptune. Many of these are in a region of space called the Kuiper Belt. When Pluto was discovered in 1930, scientists had not yet found the Kuiper Belt. Since, at the time of its discovery, Pluto seemed to be a unique new object, astronomers recognized it as a planet. Since the first detection of a Kuiper Belt Object (KBO) in 1992, hundreds more KBOs have been found. Several are nearly as large as Pluto, and one appears to be even larger than "the ninth planet". Some astronomers believe we may eventually find a dozen KBOs larger than Pluto. If Pluto had been discovered in recent years, it would have been classified as merely another large KBO.

So what is a planet? Some astronomers believe all KBOs, including Pluto, should not be considered planets. They point out that even Mercury, the 2nd smallest of the nine planets, has a volume more than eight times as large as Pluto's and is over 26 times as massive. This group believes that KBOs, including Pluto, are too small to be considered planets, and that we thus have only eight true planets in our Solar System.

Other scientists think that large KBOs should also be considered planets. If you count only objects as large as Pluto, then the large KBO with the temporary name 2003 UB313 may be the tenth planet. Over time we may find more KBOs larger than Pluto, possibly pushing the number of planets in our Solar System to 20 or higher. If you consider KBOs that are almost as big as Pluto planets, then we already have several (to dozens or hundreds, depending on how "almost as big" you mean) new planets in our system, and will surely add many more in the future as more KBOs are spotted. Some scientists have proposed calling "planets" of this variety "ice dwarf" planets.

Finally, some astronomers think that Pluto should maintain "honorary planet" status for historical reasons, but that other new KBO discoveries should not be considered "true planets". The International Astronomical Union (IAU), the official body charged with deciding such issues, is currently debating the appropriate definition of a planet. Some scientists think that the exact definition isn't important; that recognizing the types of bodies in our Solar System and understanding the history of each type of object is the more important than defining whether a given object is or is not a planet.

So what is a planet? There are a couple of points astronomers agree on. A planet must directly orbit a star. This means that moons, which orbit planets instead of stars, are not themselves planets. Secondly, planets must be large enough that gravity makes them spherical in shape. Small, odd-shaped asteroids are left out of the planet club by this criterion. Beyond these two aspects, the definition of a planet is not universally agreed upon.

How big can a planet be? Some of the gas giant planets that have been detected orbiting other stars are very large, much bigger than Jupiter. Low-mass "failed stars", known as brown dwarf stars, have masses similar to those of extremely large gas giant planets. Thus the boundaries of planethood are fuzzy at both the high and low ends of the planetary size scale. Some astronomers feel that the history and evolution of an object within a planetary system is a key to whether the object is or is not a planet. For example, some scientists say that objects which "sweep clean" their orbits of other debris left over from planetary system formation are planets; objects (like those in the Kuiper Belt) that do not clear other debris away are not planets, according to this viewpoint.

As you can see, defining "planet" is more difficult than it might first appear. Until the IAU releases an official pronouncement, competing definitions of "planet" seem likely to remain.